|

Broad Ripple Random Ripplings

The news from Broad Ripple

Brought to you by The Broad Ripple Gazette

(Delivering the news since 2004, every two weeks)

|

| Brought to you by: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Converted from paper version of the Broad Ripple Gazette (v02n09)

The Prisoner's Walk, Part I - by Joseph Foster

posted: Apr. 29, 2005

Indianapolis to Crown Point

I set out April 9th from the Monon Trail on a pilgrimage of sorts, in the tradition of troubadours from the West and haiku poets from the East carrying a notebook, mandolin and pen. The goal was to follow at least sixty percent railtrails, walking north all the way to Lake Superior in Wisconsin. I called it The Prisoner's Walk because I was hoping to discover deeper conversation with God and, in doing so, continue to scale the modernistic walls surrounding the divine simplicity of our hearts. The trip was also planned to raise awareness and donations for Poetry in the Prisons, a grassroots program in the Indianapolis area with four poets, myself included. We currently study poetry for its therapeutic benefits to the incarcerated at three prison locations of the Indiana Department of Correction. With the help of Richard Vonnegut from the Hoosier Rails to Trails Council, the journey's mission was also to provide informal research on the condition of railtrails in the northern portion of our state.

For the first 112 miles, I have found the journey to be a valuable study of written, spoken, sung and contemplative prayer. As a practicing Catholic, I made it a point to visit churches frequently, praying before the Blessed Sacrament in ten small town churches and attending mass at six. I found myself living within a heightened sense of communion with all those dedicated to spiritual labor in the past, present and future. It was a prayerful time for all Catholics as our Church transitioned from the death of our Holy Father, Pope John Paul II. I sung the Psalms out loud with the birds and the wind. I walked alone but mysteriously found myself enclosed by the invisible while meditating upon the beads and mysteries of the Rosary. In a way, it was a bit of an ascetic journey. I ate very little. As the body emptied of worldly desire, the spirit seemed to fill with song. Although this idea is nothing new, at the current moment my heart is filled with a newly born momentum.

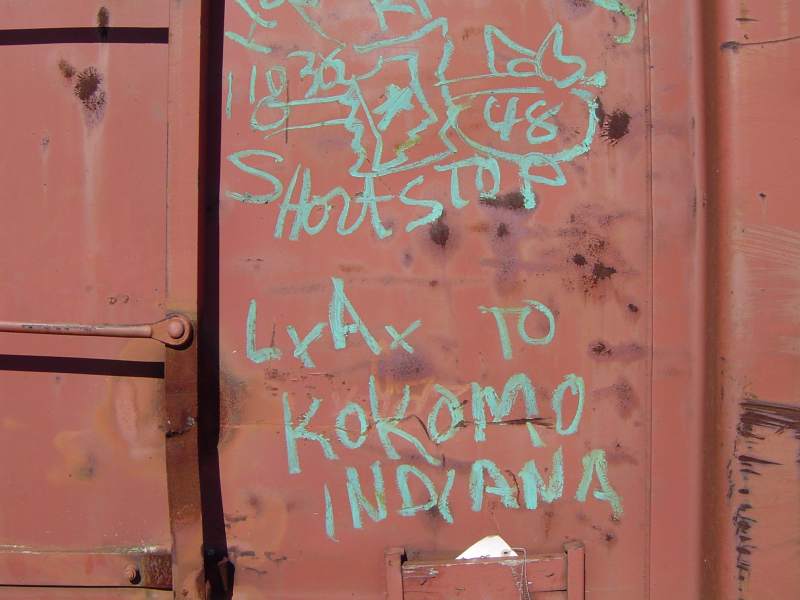

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

I had trained very little for the journey, and I highly underestimated the weight of a full backpack. A mere nine miles the first day was it for me. Fortunately, Doug and Merritt Cline of Carmel provided a delicious meal and a place to rest in their home (as well as a convenient location to ditch my mandolin along with several articles of weighty clothing!) My feet took a brutal beating on the large gravel of these Indiana railroads because I was wearing boots with thin soles. My pace improved as the days passed, and the weather was phenomenally sunny.

I walked the old Nickel Plate Railroad Trail for several days, finding peace and comfort on a light trail of short flowery weeds. I also walked several inactive lines that have rails still in place. I walked county roads, sidewalks, hallways, gravel and dirt paths. I camped in an empty silo, a shed, unplanted cornfields, backyards, and along railroad tracks amidst thorns, deer, mice, rabbit, skunk, snakes, horses, beaver, owl, spiders and poison ivy. There was a great freedom in being tossed about in the fields by strong winds of Northern Indiana with no cell phone or link to home.

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

| Brought to you by: |

|

|

|

This trip is also becoming a wonderful study of the conflict between man's desire to explore, and the already explored modern world. When I humbly compare this railtrail route (Indianapolis to Superior, Wisconsin: 700 miles) to the wilderness of the Appalachian Trail, (Springer Mountain, Georgia to Katahdin, Maine: 2,160 miles), I find many similarities with respect to our desire for solitude and unexplored territory. On the railtrail, this exploration depends more fully on the heart of the traveler. An important and subtle advantage is found in the simple nature of the formerly mentioned Midwestern journey. You see, this trip is not only about solitary man and wilderness (what's left of it), but also looking at the everyday in a new light. I merely left my front porch in Broad Ripple with a backpack strapped to my back and began a long walk along railroad tracks. There is great satisfaction in the simple beauty of this type of journey. Yes, I have been chased by trailer dogs, startled by garter snakes, and cut with barbed wire fences. Yes, I have used the gas station restroom to refill my canteen and sat around the gossip lounge listening to the retired farmers discuss the rising price of tractors. These types of significant simplicities can't be found as frequently on the Appalachian Trail. Rather, on the railtrail, I am re-exploring the already explored. I am taking a second look at the already destroyed wilderness of the Midwest and am truly fascinated by the discoveries being made within the wilderness of my own heart and within the world outside the self. These railtrails give me great hope for the future of Indiana and the Midwest in general. There are great possibilities to be found in the slow and steady transformation, one segment at a time, of old railroads into pathways for the modern Midwestern explorer. This trip has been an adventure to say the least. As these rails change, so shall the Midwestern hiker.

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

On the last two days of the recent journey I discovered, first hand, two landowners with conflicting perspectives on the growth of the railtrails in the Northern Indiana region. The first point of view was discovered haphazardly as I hiked from Monterey to North Judson on a proposed railtrail that was in the early stages of development. The stones were large because the iron rails and ties had been ripped out, which presented a rather painful obstacle to my thinly soled boots. I hiked it anyway. I had very little knowledge of the county roads, and preferred the seclusion provided by the old rail line. It was an unseasonably hot day, and the sun forced me to drink extra quantities of water. Five miles from North Judson, my canteen was empty and I was in the middle of nowhere.

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

| Brought to you by: |

|

|

|

I pressed forward, grinding every step of the way until I reached a house next to the trail. There were four Labradors in a cage that barked as I drew near. I was looking confusedly for the front door when a dark-haired man in his mid-thirties walked around the corner with his guard up. Naturally, he seemed to want an explanation for walking through his backyard and circling his house.

I apologized repeatedly for disturbing him, and hoped to put him at ease by explaining my reason for walking the old railroad. I told him I was doing a bit of informal research for Hoosier Rails to Trails on the new project and wondered if I could refill my canteen with his hose.

"Has it been turned into a public trail already?" asked the man. "See I don't really like the idea of having this trail behind my house."

I grew immediately interested despite our difference in opinion. A few miles earlier, I had wondered myself why anyone would want to inhibit the growth of these railtrails. They seemed like a valuable asset for all those in the state wishing to find quiet time, exercise and exposure to nature. When I explained my interest in his opinion, his shoulders and jaw relaxed a bit. We shook hands. He was an Italian Catholic named Christopher Ingram. Chris began to explain why he thought the trail would be an invasion of his privacy: it would continue to cut his 126 acres of family land in half, attract mischief and litter from town, and disrupt his 'sanctuary' and the delicate cycles of nature already in place around his property. He said that once he found people having sex on the old rail line near his family's house. A public trail, he thinks, would invite more such activity in his backyard. Chris made valid points. I wanted to investigate his side of the equation a bit further.

He agreed to let me pitch a tent in the forest near the house. As the sun went down, I watched the Ingram's two boys, Joseph (1st grade) and Nick (4th), run cheerfully from their grandparent's house across the field with the four family dogs. They took the grassy path just south of an unplanted field of corn. Their parents walked casually an eighth mile behind. There was a special beauty to the solitude of their home, solitude that a railtrail would undoubtedly interrupt. I was a perfect example of this interruption.

The Ingrams

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

But the Ingrams did not treat me as an interruption. Chris and his wife, Kerry, invited me into their house for a casserole dinner and conversation. According to Chris, when the railroad company forced his family (their surname back then was Pacilio) to sell the 6 acres of land for the proposed section of railroad, the contract stated that the land would be returned to the landowner following the duration of its use for rail transport. He thinks the land should have been returned to his family, making it 'one piece of property' once again. Unfortunately, I am not privy to the details of this transaction or the transaction that took place recently between the rail company and railtrail groups.

Chris Ingram

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

| Brought to you by: |

|

|

|

Despite this friction, my meeting and visit with the Ingram family provided insight into the possibility of a future peace between Midwestern railtrail hikers and family farmlands they traverse. It is important to note that special sacrifices have been made on the part of each landowner to begin to make these valuable trails a reality. I was fortunate enough to experience these concerns firsthand, and think responsibility must be taken by each hiker, as well as the law enforcement agencies of the participating counties and cities, to ensure that the rights and privacy of those living near the railtrails are respected.

On the last day of my journey to Crown Point, as I hiked State Road 8 west of Kouts, I was invited for dinner. Perry Sheets, father of four children lives down a long drive in an old farmhouse. There are abandoned railroad tracks to the north and south of their property. The Sheets love to exercise, and think it is unsafe to ride bicycles or walk on the busy roads surrounding their house. They find great hope in the possibility that one day these tracks will be railtrails. Perry's grandfather was a life-long engineer, and his father worked as a brakeman before the railroads shut down. He hopes the railtrail would prevent this legacy from disappearing completely.

After good conversation and a dinner of hamburgers, vegetables and fruit, the youngest boy, Lucas (kindergarten) asked me if I wanted to know "a secret". No one but Lucas knew what he was talking about.

"Can I show him my secret?" he asked his mother. Lucas went into his room and returned with a dandelion in a glass of water. "Here's my secret," he said with great pride and joy. "It's a baby sunflower."

In his hand, Lucas held more than a flowered weed. He held a secret to life, a secret to the future of our communities, nations and, yes, the future of our poetry, our prisoners, our future wilderness, churches and, of course, our future railtrails. He held something we all forget after the age of six. Something that has to do with the purity and simple beauty of life. Something enduring and within us. Something we must be reminded of almost daily lest we forget. Lucas shared with me his greatest treasure. It was a gift I can never spend or run out of because it is endless in it's charity.

Perry Sheets drove me 12 miles that night to my parent's home in Crown Point. My father was planting wine rose bushes when we pulled up. Mom was out back with my sister and the twin granddaughters. It was a warm and breezy night. I felt the silky hair of my two-year-old niece. We looked up at the sky together.

"Do you know how long it would take to walk to the moon?" I asked.

"Walk to the moon," she nodded, repeating my words.

"I think it would take longer than my life and your life put together," I said, noticing the moonlight in her stare. For a moment, the iris of her wide eyes let me in. She let me walk on the surface of something pure, ancient and innocent. In my arms I may have held the moon itself. That night I discovered in her eyes the infinite sky stretching far and beyond all human understanding. I felt like a pilgrim who had walked 112 miles to fall silent where I had begun - in the eyes of a child - the beautiful secret we are all given at birth and spend our lives being taught by the world to forget. She leaned back into my chest. We lay in the grass for several minutes listening to God.

For more information on the walk or Poetry in the Prisons please email Joseph Foster at poetryintheprisons@yahoo.com or visit www.mvsc.k12.in.us/mhs/poetry/. If you would like to make tax deductible donation to the Poetry in the Prisons project please make checks payable to Indianapolis Peace and Justice Center and mail to Poetry in the Prisons; 6166 Carrollton Ave; Indpls, IN 46220.

Wide-open field

You have placed me before a wide-open field

so I may begin to know your wide-spreading presence.

The hawk and I trade glances in a wingspan,

wind-surfing these currents of time.

My back leans against this tree, I sit long,

allowing her shadow to pass over mine.

I am gone now.

I am dissolved in the hours, somewhere within the return of your gaze.

I am within your eye looking into mine.

I allow you to penetrate

the hidden boundaries of my heart,

remembering the treasure I locked up one day

and whispered to no one.

I realize these secrets were once whispered

by you

when you breathed into me.

I realize you have been there all along,

defining my heart.

I realize I have always belonged to you

at home, when I sit

spreading far and wide

within the farthest longing of my chest.

I realize that somewhere within the first whisper of my own name,

this wide open field

and the haunt of this wind

were given the wilderness of your expanding breath.

A century goes by quickly

and soon I have traveled far back

to a land before these rails, soon

I have joined you in the pauses of the wind

and too soon the wind becomes the last train

to ride this plane around the earth.

Joseph Foster 2005

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

image courtesy of Joseph Foster

|

|

|

| Brought to you by: |